What’s Access doing when an user make changes to data on an ODBC linked table?

Our ODBC tracing series continues, and in this fourth article we will explain how to insert and update a data record in a recordset, as well as the process of deleting a record. In the previous article, we learned how Access handles populating the data from ODBC sources. We saw that the recordset type has an important effect on how Access will formulate the queries to the ODBC data source. More importantly, we found that with a dynaset-type recordset, Access performs additional work to have all the information required to be able to select a single row using a key. This will apply in this article where we explore how data modifications are handled. We will start with insertions, which is the most complicated operation, then move on to updates and finally deletions.

Inserting a record in a recordset

The insertion behavior of a dynaset-type recordset will depend on how Access perceives the keys of the underlying table. There will be 3 distinct behaviors. The first two deals with handling primary keys that are autogenerated by the server in some way. The second is a special case of the first behavior which is applicable only with SQL Server backend using an IDENTITY column. The last deals with the case when the keys are provided by the user (e.g. natural keys as part of data entry). We will start with the more general case of server-generated keys.

Inserting a record; a table with server-generated primary key

When we insert a recordset (again, how we do this, via Access UI or VBA does not matter), Access must do things to add the new row to the local cache.

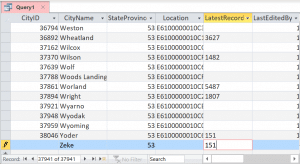

Inserting a new record into an ODBC linked table.

The important thing to note is that Access has different insert behaviors depending on how the key is set up. In this case, the Cities table does not have an IDENTITY attribute but rather uses a SEQUENCE object to generate a new key. Here’s the formatted traced SQL:

SQLExecDirect: INSERT INTO "Application"."Cities" ( "CityName" ,"StateProvinceID" ,"LatestRecordedPopulation" ,"LastEditedBy" ) VALUES ( ? ,? ,? ,?) SQLPrepare: SELECT "CityID" ,"CityName" ,"StateProvinceID" ,"Location" ,"LatestRecordedPopulation" ,"LastEditedBy" ,"ValidFrom" ,"ValidTo" FROM "Application"."Cities" WHERE "CityID" IS NULL SQLExecute: (GOTO BOOKMARK) SQLExecDirect: SELECT "Application"."Cities"."CityID" FROM "Application"."Cities" WHERE "CityName" = ? AND "StateProvinceID" = ? AND "LatestRecordedPopulation" = ? AND "LastEditedBy" = ? SQLExecute: (GOTO BOOKMARK) SQLExecute: (MULTI-ROW FETCH)

Traced ODBC SQL after an insert into an ODBC linked table.

Note that Access will only submit columns that were actually modified by the user. Even though the query itself included more columns, we only edited 4 columns, so Access will only include those. That ensures that Access does not interfere with the default behavior set for the other columns that the user did not modify, since Access has no specific knowledge about how the data source will handle those column. Beyond that, the insert statement is pretty much what we would expect.

The second statement, however, is a bit odd. It selects for WHERE "CityID" IS NULL. That seems impossible, since we already know that the CityID column is a primary key and by definition cannot be null. However, if you look at the screenshot, we never modified the CityID column. From Access’ POV, it is NULL. Most likely, Access adopts a pessimistic approach and won’t assume that the data source will in fact adhere to SQL standard. As we saw from the section discussing how Access selects an index to use to uniquely identify a row, it might not be a primary key but merely an UNIQUE index which may allow NULL. For that unlikely edge case, it does a query just to make sure that the data source did not actually create a new record with that value. Once it has examined that there were no data returned, it then tries to locate the record again with the following filter:

WHERE "CityName" = ? AND "StateProvinceID" = ? AND "LatestRecordedPopulation" = ? AND "LastEditedBy" = ?

Finding the newly inserted record.

which were the same 4 columns the user actually modified. Since there was only one city named “Zeke”, we got only one record back, and thus Access can then populate the local cache with the new record with same data as the data source has it. It will incorporate any changes to other columns, since the SELECT list only includes the CityID key, which it will then use in its already prepared statement to then populate the entire row using the CityID key.

Inserting a record; a table with autoincrementing primary key

However, what if the table comes from a SQL Server database and has an autoincrementing column such as IDENTITY attribute? Access does behave differently. So let’s create a copy of the Cities table but edit so that the CityID column is now an IDENTITY column.

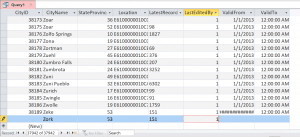

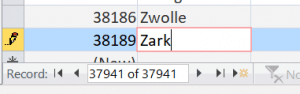

Inserting into an ODBC linked table with an IDENTITY primary key. Note the (New) placeholder that wasn’t previously present.

Let’s see how Access handles this:

SQLExecDirect: INSERT INTO "Application"."Cities" ( "CityName" ,"StateProvinceID" ,"LatestRecordedPopulation" ,"LastEditedBy" ,"ValidFrom" ,"ValidTo" ) VALUES ( ? ,? ,? ,? ,? ,?) SQLExecDirect: SELECT @@IDENTITY SQLExecute: (GOTO BOOKMARK) SQLExecute: (GOTO BOOKMARK)

Traced ODBC SQL for insert with an autoincrementing column.

There is significantly less chatter; we simply do a SELECT @@IDENTITY to find the newly inserted identity. Unfortunately, this is not a general behavior. For example, MySQL supports the ability to do a SELECT @@IDENTITY, however, Access will not provide this behavior. PostgreSQL ODBC driver has a mode to emulate SQL Server in order to trick Access into sending the @@IDENTITY to PostgreSQL so it can map to the equivalent serial data type.

Inserting a record with an explicit value for primary key

Let’s do a 3rd experiment using a table with a normal int column, without an IDENTITY attribute. Though it’ll still be a primary key on the table, we’ll want to see how it behaves when we explicitly insert the key ourselves.

SQLExecDirect: INSERT INTO "Application"."Cities" ( "CityID" ,"CityName" ,"StateProvinceID" ,"LatestRecordedPopulation" ,"LastEditedBy" ,"ValidFrom" ,"ValidTo" ) VALUES ( ? ,? ,? ,? ,? ,? ,? ) SQLExecute: (GOTO BOOKMARK) SQLExecute: (MULTI-ROW FETCH)

Traced ODBC SQL for insert with an explicit value set for the primary key.

This time around, there is no extra gymnastics; since we already provided the value for the primary key, Access knows that it does not have to try and find the row again; it just executes the prepared statement for resynchronizing the inserted row. Going back to the original design where the Cities table used a SEQUENCE object to generate a new key, we can add a VBA function to fetch the new number using NEXT VALUE FOR and thus populate the key proactively to get us this behavior. This more closely approximates how Access database engine works; as soon as we dirty a record, it fetches a new key from the AutoNumber data type, rather than waiting until record has been actually inserted. Thus, if your database uses SEQUENCE or other ways of creating keys, it may pay off to provide a mechanism of fetching the key proactively to help cut out the guesswork we saw Access doing with the first example.

Updating a record in a recordset

Unlike inserts in previous section, updates are relatively easier because we already have the key present. Thus, Access usually behave more straightforward when it comes to update. There are two major behaviors we need to consider when updating a record which depends on the presence of a rowversion column.

Updating a record without a rowversion column

Suppose we modify only one column. This is what we see in ODBC.

SQLExecute: (GOTO BOOKMARK) SQLExecDirect: UPDATE "Application"."Cities" SET "CityName"=? WHERE "CityID" = ? AND "CityName" = ? AND "StateProvinceID" = ? AND "Location" IS NULL AND "LatestRecordedPopulation" = ? AND "LastEditedBy" = ? AND "ValidFrom" = ? AND "ValidTo" = ?

Traced ODBC SQL for an update on the ODBC linked table.

Hmm, what’s the deal with all those extra columns we didn’t modify? Well, again, Access has to adopt a pessimistic outlook. It has to assume that someone possibly could have had changed the data while the user was slowly fumbling through the edits. But how would Access know that someone else changed the data on the server? Well, logically, if all columns are exactly the same, then it should have had updated only one row, right? That’s what Access is looking for when it compares all the columns; to ensure that update only will affect exactly one row. If it finds that it updated more than one row or zero rows, it rollbacks the update and return either an error or #Deleted to the user.

But… that’s kind of inefficient, isn’t it? Furthermore, this could bring problem if there are server-side logic that might change the values input by the user. To illustrate, suppose we add a silly trigger that changes the city name (we don’t recommend this, of course):

CREATE TRIGGER SillyTrigger

ON Application.Cities AFTER UPDATE AS

BEGIN

UPDATE Application.Cities

SET CityName = 'zzzzz'

WHERE EXISTS (

SELECT NULL

FROM inserted AS i

WHERE Cities.CityID = i.CityID

);

END;

Silly trigger that modifies the city name.

So if we then try to update a row by changing the city name, it will seem to have succeeded.

Updating a row on a table which will succeed.

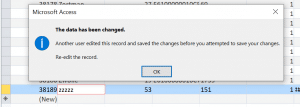

But if we then try to edit it again, we get an error message with refreshed message:

Error message shown when trying to updating the row after saving the last update.

This is the output from sqlout.txt:

SQLExecDirect: UPDATE "Application"."Cities" SET "CityName"=? WHERE "CityID" = ? AND "CityName" = ? AND "StateProvinceID" = ? AND "Location" IS NULL AND "LatestRecordedPopulation" = ? AND "LastEditedBy" = ? AND "ValidFrom" = ? AND "ValidTo" = ? SQLExecute: (GOTO BOOKMARK) SQLExecute: (GOTO BOOKMARK) SQLExecute: (MULTI-ROW FETCH) SQLExecute: (MULTI-ROW FETCH)

Traced ODBC SQL for an update and attempted edit.

It’s important to note that the 2nd GOTO BOOKMARK and the subsequent MULTI-ROW FETCHes did not happen until we get the error message and dismissed it. The reason is that as we dirty a record, Access performs a GOTO BOOKMARK, realize that the data returned no longer matches what it has on the cache, which cause us to get the “The data has been changed” message. That prevents us from wasting time editing a record that is doomed to fail because it’s already stale. Note that Access would also eventually discover the change if we gave it enough time to refresh the data. In that case, there would be no error message; the datasheet would simply be updated to show the correct data.

In those cases, though, Access had the right key so it had no problem discovering the new data. But if it’s the key that is fragile? If the trigger had changed the primary key or the ODBC data source did not represent the value exactly as Access thought it would, that would cause Access to paint the record as #Deleted since it cannot know whether it was edited by the server or someone else versus if it was legitimately deleted by someone else.

Updating a record with rowversion column

Either way, getting an error message or #Deleted can be quite annoying. But there is a way to avoid Access from comparing all columns. Let’s remove the trigger and add a new column:

ALTER TABLE Application.Cities ADD RV rowversion NOT NULL;

Adding rowversion to the Cities table.

We add a rowversion which has the property of being exposed to ODBC as having SQLSpecialColumns(SQL_ROWVER), which is what Access needs to know that it can be used as a way to version the row. Let’s look at how updates work with this change.

SQLExecDirect: UPDATE "Application"."Cities" SET "CityName"=? WHERE "CityID" = ? AND "RV" = ? SQLExecute: (GOTO BOOKMARK)

Updating a row in a table with a rowversion column.

Unlike the previous example where Access compared the value in each column, whether the user edited it or not, we only update the record using the RV as the filter criteria. The reasoning is that if the RV still has the same value as the one that Access passed in, then Access can be confident that this row wasn’t edited by anyone else because if it was, then the RV‘s value would have changed.

It also means that if a trigger altered the data or if SQL Server and Access didn’t represent one value exactly the same way (e.g. floating numbers), Access will not balk when it re-selects the updated row and it comes back with different values in other columns that the users didn’t edit.

NOTE: Not all DBMS products will use the same terms. As an example, MySQL’s timestamp can be used as a rowversion for ODBC’s purposes. You will need to consult the product’s documentation to see if they support the rowversion feature so that you can leverage this behavior with Access.

Views and rowversion

Views are also impacted by presence or absence of a rowversion. Suppose we create a view in SQL Server with the definition:

CREATE VIEW dbo.vwCities AS SELECT CityID, CityName FROM Application.Cities;

View definition based on a table that has a rowversion column that is not included.

Updating a record on the view would revert to the column-by-column comparison as if the rowversion column didn’t exist on the table:

SQLExecDirect: UPDATE "dbo"."vwCities" SET "CityName"=? WHERE "CityID" = ? AND "CityName" = ?

Updating a view with a rowversion column included in the view.

Therefore, if you need the rowversion-based update behavior, you should take care to ensure that the rowversion columns are included in the views. In the case of a view that contains multiple tables in joins, it’s best to include at least the rowversion columns from table(s) where you intend to update. Because typically only one table can be updated, including only one rowversion may suffice as a general rule.

Deleting a record in a recordset

The deletion of a record behaves similarly to the updates and also will use rowversion if available. On a table without a rowversion, we get:

SQLExecDirect: DELETE FROM "Application"."Cities" WHERE "CityID" = ? AND "CityName" = ? AND "StateProvinceID" = ? AND "Location" IS NULL AND "LatestRecordedPopulation" = ? AND "LastEditedBy" = ? AND "ValidFrom" = ? AND "ValidTo" = ?

Deleting a record from a table without a rowversion column.

On a table with a rowversion, we get:

SQLExecDirect: DELETE FROM "Application"."Cities" WHERE "CityID" = ? AND "RV" = ?

Deleting a record from a table with a rowversion column.

Again, Access has to be pessimistic about deleting as it is about updating; it would not want to delete a row that was changed by someone else. Thus it uses the same behavior we saw with updating to guard against multiple users changing same records.

Conclusions

We’ve learned how Access handles data modifications and keep its local cache in synchronization with the ODBC data source. We saw how pessimistic Access was, which was driven by the necessity to support as many ODBC data sources as possible without relying on specific assumptions or expectations that such ODBC data sources will support a certain feature. For that reason, we saw that Access will behave differently depending on how the key is defined for a given ODBC linked table. If we were able to explicitly insert a new key, this required the minimal work from Access to resynchronize the local cache for the newly inserted record. However, if we allow the server to populate the key, Access will have to do additional work in background to resynchronize.

We also saw that having a column on the table that can be used as a rowversion can help cut down on chatter between Access and the ODBC data source on an update. You would need to consult the ODBC driver documentation to determine whether it supports the rowversion at ODBC layer and if so, include such column in the tables or the views before linking to Access to reap the benefits of rowversion-based updates.

We now know that for any updates or deletions, Access will always try to verify that the row was not changed since it was last fetched by Access, to prevent users from making changes that might be unexpected. However, we need to consider the effects arising from making changes in other places (e.g. server-side trigger, running a different query in another connection) which can cause Access to conclude that the row was changed and thus disallow the change. That information will help us analyze and avoid creating a sequence of data modifications that may contradict Access’ expectations when it resynchronizes the local cache.

In the next article, we will look at the effects of applying filters on a recordset.

Get help from our Access Experts today. Call our team on 773-809-5456 or drop us an email at [email protected].